Of the three military branches, Army, Navy, Air Force (Sorry Marines, as good as you think you are and as good as you have been, you remain a subordinate part of the Navy and really have become an unnecessary part of the military force because you just duplicate the mission of the other services, even if you are good.), the Navy seems most unique to me.

One of my best friends, Marty Linville, an Army artillery wizard who received a well-deserved Silver Star for his heroic action in Vietnam as the commander of an artillery unit, and i have often discussed the difference between enlisted personnel and officers, Army and Navy.

The biggest difference, in which the Army’s side of this difference also includes the Navy’s Special Forces warriors, the SEALS is that the true, original Navy officers, now known as Surface Warfare officers (what a bunch of malarky) is their expertise in driving ships. Their other, equally important purpose is to lead or manage (or both) their subordinates, at least in rank. Officers in the Army and SEALS, especially the junior officers, are out in the field waging war while leading their subordinates.

Marty and i agree the differences in the historical structure comes from the differences in role. Obviously, there are some historical and tradition elements that foster the difference. The Navy, the surface warfare kind, seems to draw more distinction in the rank divisions of officer, chief petty officer, and other enlisted.

Their uniforms announce that difference. But in the Navy, it is significant, although the new Navy seems intent on wiping out any differentiation, both symbolically with uniforms and literally with less separation between the ranks. With the advances in technology and many other things, this merging may be necessary. i wouldn’t know. i’m old school. As in old.

i have formed a long distance bond with a number of sailors on my first ship, the USS Hawkins (DD-873). i reported aboard in April 1968, flying from Rota to Malaga, Spain and coming aboard as she was on her way back from a nine-month Mediterranean deployment to her homeport of Newport, Rhode Island. i had completed OCS in early February, spent two months in Key West attending the Anti-Submarine Officer’s School before flying out of Charleston with my entire belongings: my uniforms, a small civilian wardrobe, and a grunch of books, all in a plywood 2 x 2 x 4 foot cruise box that weighed in the neighborhood of a ton.

i was slated to be the ASW officer, but the resident ASWO was not leaving until early October, so i was assigned the first lieutenant’s billet for the return, the summer of minimal local operations until the September beginning of a six-month overhaul when i took over as ASW officer.

Those first six months were a crash learning course in how Navy ships at the time really worked. The “Navy way” was continually emblazoned in my head for the next twenty-two years. A great deal of that learning curve concerned the differences between the enlisted, the chiefs, and the officers. Actually, there was another division: the “leading petty officers” or “LPO’s.”

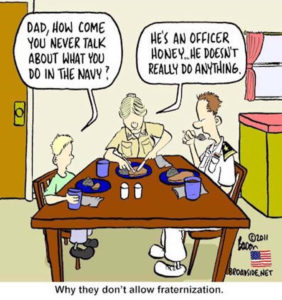

The system worked well even though the different groups made fun of the others. A great example of that is the cartoon taking a shot across the bow at officers, Norm O’Neal, a radarman (RD) at the time and now a close friend through email and social media, sent me last week:

Norm, this one wouldn’t let me “reply to all,” the officers said this about a lot of chiefs.

To which, Norm replied, “Ouch.”

To which i added:

Actually, Norm, as it is with nearly all situations, there are good people and bad people in every level of every organization.

My first chief petty officer was the Hawkins’ BMC Jones. He saved my ass on several occasions. He was a small, thin, wiry, gnarly, old chain-smoking chief from Arkansas. After teaching this ensign the ropes, he retired the Monday after the change of command on the Hawk in August 1968 (speaking of good and bad, there was the CO who made the deployment, the screamer whose name i can’t recall right now being relieved by Max Lasell, who remains one of the top three of the CO’s under whom i served, and that’s another story).

But Chief Jones was relieved by a short, portly, old BMC with thick white hair whose name i also can’t remember. He was the first of many chiefs who worked for or with me officers called “ROADS Scholar” for Retired On Active Duty. You could tell them by the permanent crook they had in their pointer finger from holding on to their coffee cup they used while they spent about 95% of their time in the chiefs’ mess.

But that was only part of my crash education about Chief Petty Officers on the Hawk. i learned why Chief Petty Officers, a unique position in the military services, were so important. Through my remaining twenty-two years, this idea of chiefs being different was continually emphasized. For good reason.

My initial realization of the difference was from the get-go. i had wondered since i first became connected to the Navy when i began my NROTC scholarship tragedy at Vanderbilt, why senior enlisted had uniforms more like officers than the other enlisted. Although i was slowly learning why through OCS in Newport, Rhode Island, ASW school in Key West, and two weeks in Rota waiting to join my new ship, the difference slowly was becoming apparent to me.

But on the Hawkins, it became quite clear.