This is a story sort of wrapping up Willie Nod. i wrote it recently. i have sent it to my grandson already.

i haven’t found any more Willie Nod poems but expect i will run across some in some cranny of all the files i have. i intend to write some more. But i thought you might want know how Willie Nod ended up…at least temporarily.

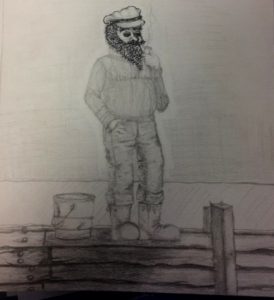

i should stress this is the first draft and Sarah’s drawing is her first draft. As with all Willie Nod works, the writing is mine, copyright jim jewell 2017, and the drawings are Sarah’s, all copyright Sarah Jewell 2017.

For Sam: A Story of Long Ago With Some Semblance of Truth

Sam,

This is a story that began in my mind a long time ago after one of the most difficult times in my life and just before one of the most magical times in my life.

The hut in this story was real. In 1969, that hut was off of First Beach right behind the house where i rented the upstairs apartment. I think someone actually lived in it.

It was down the rocks from the back yard of my apartment, an old big house really, in Newport, Rhode Island.

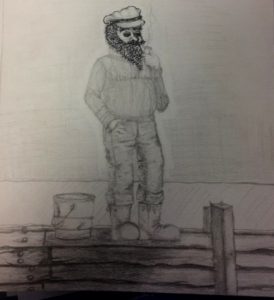

A great deal of this is fiction, but it is based on actual places and things in my mind i still believe.

It was really just a hole dug a bit into the hard sand underneath the rocks someone had cleared around the hut’s front facing the beach. The roof was makeshift, made from corrugated tin sheet the builder apparently found somewhere. The rocky shore slanted toward the waters of Newport’s Easton Bay with First Beach to the right, or northward. The tin roof was almost unrecognizable as tin with seaweed and seagull droppings piled upon the roof and only the very front edge of the tin was visible, shakily held up by four by four timbers of ancient vintage. There was a chimney, a metal pipe sticking up near the front with a rain cap of tin beaten into an upside down vee. Old colored glass fishing floats and ramshackle, worn wooden lobster pots littered the rocks above and on the sides of the hut.

Jake Wilson noticed it right after he had rented the upstairs apartment in the large, run-downed old big house at the end of Tuckerman Avenue, which circumvented the point jutting out south into the Atlantic between First and Second beaches.

But Jake had rented the apartment because it was affordable, less expensive than the nicer apartments in Middletown and downtown Newport. He had stumbled onto this place and fallen in love with it.

The small porch off the bedroom’s apartment looked straight across the bay to “The Breakers,” Cornelius Vanderbilt, II’s famous summer mansion. The apartment living room was about twenty-five feet long and fifteen feet wide with an ornate fireplace at the north end. The fireplace inlaid, ornate tiles were hand painted. The rest of the apartment was cramped to say the least. The bedroom itself could barely hold the double-bed. The kitchen was the size of a narrow closet and the kitchen sink served double as the bathroom sink. The bathroom itself was just big enough to turn around amid the shower and the toilet.

However, the view of mansion row across the bay, the rocky shoreline, and the feeling of being next to the sea appealed to Jake. He would wake up in the morning and immediately walk out on the porch and take in the view. It mattered not to him if it was sunny, calm, cloudy, stormy with driving rain, hot or cold. In the evening on return from his ship, he would go directly to the porch and again survey his view from the beach where folks might still be digging for quahogs in the wet sand to the Cliff Walk where couples would be walking past sunset to the mansions down Ochre Point to Land’s End on Sheep’s Point, and of course, the ocean. Before he hit the rack in the evening, Jake once more would return to the port and take in the night lights.

It was three weeks before Jake noticed the hut. It was a warm autumn Saturday morning when he walked out onto his beloved porch with his cup of coffee after breakfast. He was testing the weather, thinking he might drag a chair out on the porch and read through the morning. The weather was just fine, dry, clear, warmer than usual for that time of year. Jake scanned the view he had come to love.

He then noticed the pipe chimney and beaten rain cap for the first time. He spied the lobster pots and glass floats before but assumed they were just debris or possibly jetsam that had floated ashore and up into the rocks at high tide. But seeing the chimney, Jake looked closer. He made out the roof. He wondered when the structure might have been built and why. He guessed it was a really old, abandoned place, maybe even once a playhouse for the children of previous residents when it was a home, not broken into apartments. Jake’s telephone rang inside. He went in to answer and forgot for the time being about the strange construction.

About a week later when the weather had turned cooler and sea winds were brittle and harsh, Jake walked out on the porch in his rain gear. He was a Navy officer and like to think of being on the open bridge of a ship in bad weather. As he was staring out at sea from his porch, he caught a flimsy trail of smoke out of the corner of his eye. When he turned to see the source of the smoke, he discovered it was coming from the pipe chimney of the hut. Someone was living there or at least was using it for a temporary shelter from the wind and the cold.

The next Sunday, he decided to check out the hut and figure out what was going on. The hut sat halfway up the shoreline’s rocky slope. The rocks were slippery, especially when wet. Just seeing the smoke wasn’t worth finding out more about the hut. It was just a relic, he thought, probably someone walking the beach and decided to take a break from the cold. It wasn’t worth the risk of falling to find out. But during the week, Jake stopped at The Tavern on Memorial Avenue for a beer after coming from the ship. He sat at the bar and began talking to a local sitting next to him. The guy told him about the rumors about the hut. He said a whole bunch of folks thought there was a ghost haunting the place. Others said they had seen a bedraggled old man wandering around the beaches and claimed he, whoever he was, lived in that hut. Now Jake wanted to know just exactly what was happening in that hut. He guessed it was most likely a homeless man who holed up in the shelter during bad weather. But he wanted to know for sure and decided he would risk scaling down those rocks to find out.

That Sunday, Jake finished his breakfast of sausage, eggs, and grits (he had found the grits and Tennessee sausage in a small grocery on Thames). He sat in the middle of the large living room with the Sunday edition of The New York Times spread across the floor. He pored over each section until the sun had warmed the autumn morning. When he had finished his reading and his coffee, he pulled on his sneakers, he went down the stairs and out the back entrance to the house, which was actually the front of the house because it faced the bay and not Tuckerman Avenue.

Jake carefully maneuvered down the slick rocks until he reached the side of the hut. “Halloo,” he yelled, “Anybody here?” When there was no answer, he shouted the same query again, only louder.

With no answer again, Jake slid further down and across the rocks to the front of the hut. The old, faded-white door, like it used to be an interior door, was ajar. Jake, inching closer carefully, peered inside. He could make out the “Ben Franklin” stove connected to the old pipe chimney. Further back in the hut was an old canvas cot with blankets and pillows piled high. Jake moved a little closer and saw an old wooden sea chest with brass bindings next to the cot.

Feeling a bit embarrassed like he was intruding into someone’s home, Jake climbed back up the rocks. Once back on the house lawn, he peered up and down the shoreline but saw no one. He gave up and went back to his apartment.

Jake continued to watch the hut closely at every opportunity. Several nights, he spotted smoke coming from the hut’s chimney. It was always late. He never saw anyone coming in or out.

After about a month, Jake was ready for his enjoyable Sunday morning routine again. He had eaten his breakfast of eggs, grits, and sausage. Before breaking out his copy of the Sunday Times, he grabbed his cup of coffee and walked out on his porch. As usual, he scanned the view. As he looked toward First Beach, he spotted the man by the water’s edge below the hut.

As quickly as he could, Jake got dressed, ran down the stairs, ran across the lawn and as quickly as he deemed safe climbed down the rocks.

Halfway down, he stopped to get his bearings. He again located the man at the water’s edge. Jake gasped when he realized the man was leaning over the water. Immediately below the man’s head was a dolphin. The two seemed to be talking to each other although, because of the sound of the surf, Jake couldn’t be sure they were talking.

He studied the man and the mammal. The man appeared to be old but was lithe and agile in his movement. The man had on worn jeans and boat shoes, and a heavy wool sweater. His very long beard was dark rust. His head was covered with a sailor’s heavy weather wool knit cap, a watch cap the sailor’s called them. As the dolphin bobbed up and down, his nose got very close to the man’s face. Jake now was certain the two were talking to each other.

Jake moved closer and yelled, “Halloo!”

The man and the dolphin turned toward Jake. It seemed to him they nodded okay. He moved closer.

Before he got next to them, the old man greeted, “How are you doing on this fine day?”

“Fine,” Jake replied, “How about you?”

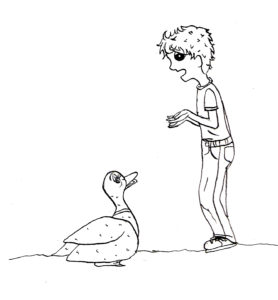

“We are just super fine,” the man nodded toward the dolphin who nodded his head and made a dolphin squeal. The man added, nodding toward the dolphin again, “This is my friend Eddie.”

Not quite sure just exactly he should respond to a man and a dolphin, Jake responded, “It’s nice to meet both of you.”

“Eddie says it’s nice to meet you as well but he needs to get back to fishing,” the man translated.

Jake was sure Eddie, the dolphin rose a foot or so more out of the water, nodded his head once or twice, twisted as he dove into the water and disappeared.

Still a bit stunned and a bit unsure of himself, which most of us would be if we met a man talking to a dolphin, Jake apologized, “I’m sorry if I bothered you and interrupted your time with…er, Eddie. But I saw you down here from my apartment up there, and I was curious about what was going on and wondering if you were the one who stayed in that hut up there,” nodding his head up the rocks toward the hut.

“No problem with Eddie; no need to apologize,” the man said, “He and I meet here quite often and talk about things.

“And yes, that is my home up there, also nodding towards the hut.

As they talked, Jake studied the man. He decided the man was not as old as he looked initially, maybe in his fifties, early sixties.

“Wow,” Jake exclaimed, “How long have you lived there?”

“Well, let’s see,” the man mulled, “The original owner of that house where you live…I think his name was McDougall, gave me the okay to dig out this place, make the hut, such as it is, and stay as long as I wanted. I think I have the deed, he wrote out, maybe in that sea chest, but never no mind, I guess to answer your question, I’ve been living here, off and on, for about twenty-five, thirty years.”

“So what do you do?” Jake asked, “How did you live here that long?”

The man expounded:

“Well, when I finally grew up, I joined the Navy and sailed on a bunch of ships. Can’t complain. I saw a whole bunch of the world in about ten years, met a bunch of different animals from all over.

“But I got tired of it, and when my last Navy ship, a destroyer, pulled back into here after a deployment, I just said ‘adieu’ and gave it up.

“I worked on fishing boats and chartered sailboats for a while, but that only lasted for about five years.

“I’ve been sort of wandering around since then. But I always seem to end up back here. This is really the only real home I’ve had since growing up. And it’s one of the few places left where I can talk to my friends.”

Jake was trying to absorb the man’s story, trying to decide what was factual and what was fantasy.

“So what friends do you talk to?” he asked.

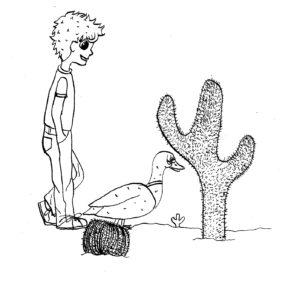

“Oh, not as many as I used to,” the man replied and continued, “one of my very favorites, the old silver bird, sort of gave up on me. When I got older, I couldn’t hold on as well. So he and I decided I shouldn’t ride with him on his flights. He just sort of left like Rabbit Smith left me out in the desert a bunch of years ago.

“But there were others,” the man continued, “Most left because I got older. They said they couldn’t trust a grownup. Grownups, they said, are selfish, not as honest, more concerned about getting rather than getting along, they said. They said grownups like to blame others for their problems and just don’t get along with each other, plus they are pretty mean to animals even when they are trying to be helpful.

“Of course, my animals didn’t have it exactly right. They, like us humans, never get it exactly right. Like Rabbit Smith, I think i finally figured out the problem: There’s a difference between caring and worrying. And animals, just like humans, can’t quite figure that difference. At least, Rabbit Smith didn’t worry that much.”

“But anyways, the animals started to not trust me because I became a grownup. So they left.”

“Whoa, whoa,” Jake responded, “Who are these people? The bird who wouldn’t take you flying, was he a pilot? And this Rabbit Smith guy, was he a sailor? And if so, what were you two doing in the desert?”

“Oh, I guess you don’t understand,” the man acknowledged, “The bird really was a silver bird, beautiful, kind old fellow. He used to put me on top of his wings and take me flying. Oh, how we loved to fly together. The first animal I really talked to, outside my dog and cat, of course.

“And Rabbit Smith?” He was a long-eared, Southwestern jack rabbit. Crazier than a loon. Hard headed old coot. But he was a great friend.

“You see, when I was young, I discovered I could talk to a lot of animals. Now I only talk to a few. My dog and cat, and of course, Eddie.”

Jake was flabbergasted, but he decided to trust the man and not question him much further. The man asked Jake about who he was, where he came from, and what he did for a living. They talked for an hour or so. Then Jake climbed back up the rocks and went to his apartment where he turned on the television and watched the Sunday afternoon professional football game.

Jake went down and talked to the man sevneral more times after that. Twice, it was when Eddie was there. Jake would listen to the strange sounds between the man and the dolphin. Then the man would translate. Jake couldn’t come close to learning how to talk to the dolphin.

After a while, Jake’s ship deployed to the Mediterranean for ten months. He had to give up his apartment. When his ship returned, Jake drove over to Tuckerman Avenue and parked on the street next to his old apartment. He walked around the house to the rocky bank down to the shore. He scaled down the rocks to the hut.

There was no sign of the man. The hut was abandoned. The cot and the sea chest were gone. The chimney was broken and the whole place was in disarray as if no one had lived there in quite a while. There was graffiti scrawled across the old, now broken door.

Jake stood outside the hut, staring. He didn’t look at the beach or the mansions across the bay. He looked out to the Atlantic Ocean and wondered where the man had gone.

Staring at the ocean, Jake remembered one of his last meetings with the man. The man had scratched his long, thick beard and then talked about what Rabbit Smith had told him when the two had spent time together in the desert:

“‘Well, Willie,’ Rabbit Smith said to me, ‘if you don’t have a lot of other people to worry about, you don’t worry about yourself so much.’

“Rabbit Smith went on, ‘I’ve never been too much of a worrier; so one day when I was all wrapped up in worrying about all of those other scrawny, bug-eyed rabbits, I decided I was worrying too much. Took off; headed east.’”

“Rabbit Smith went on, ‘I’ve never been too much of a worrier; so one day when I was all wrapped up in worrying about all of those other scrawny, bug-eyed rabbits, I decided I was worrying too much. Took off; headed east.’”

Jake wondered if that was what the man had done: got to thinking about worrying about Jake and taken off.

Jake then remembered in their last discussions, Jake had finally asked the man his name. Jake remembered thinking it was a weird name, but seemed fitting for the man, who had replied:

“Willie Nod.”