This is a slight rewrite from about fifteen years ago. A very special moment in my life initiated my writing this. i don’t recall if it was newspaper column or i simply wrote it.

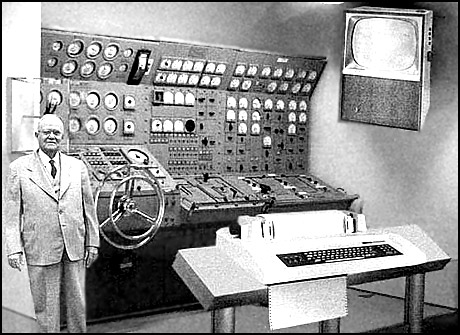

Recently, Mike Dixon, a close Lebanon friend, basketball one-on-one opponent, baseball teammate, and of several other connections sent me an email containing a photo purported to be a Popular Mechanics cover from the 1950’s. The photo showed a massive control board with many gadgets, dials, and meters. The email falsely claimed the photo was Rand Corporation’s idea of a home computer in the future 2004. A couple of my old Navy connections had sent the item to me previously, and i had checked it out to find out it was a hoax. The photo was actually a control panel for the propulsion plant of a nuclear submarine used for training prospective submarine officers. i informed Mike of this information. When he sent a not of appreciation, i provided him the following response:

Recently, Mike Dixon, a close Lebanon friend, basketball one-on-one opponent, baseball teammate, and of several other connections sent me an email containing a photo purported to be a Popular Mechanics cover from the 1950’s. The photo showed a massive control board with many gadgets, dials, and meters. The email falsely claimed the photo was Rand Corporation’s idea of a home computer in the future 2004. A couple of my old Navy connections had sent the item to me previously, and i had checked it out to find out it was a hoax. The photo was actually a control panel for the propulsion plant of a nuclear submarine used for training prospective submarine officers. i informed Mike of this information. When he sent a not of appreciation, i provided him the following response:

When i first saw the photo and the claim from someone else a long time ago, i questioned it primarily because it did look more like a FRAM engineering plant’s main control board in the forward engine room but a bit more sophisticated. i then started checking it out and discovered the photo’s actual source.

In case you don’t recall, one of my Navy tours was as chief engineer or “CHENG” on the destroyer, USS Hollister (DD 788). FRAM’s were WWII vintage destroyers “modernized” (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization) in the 1950’s and early 60’s by taking off the original superstructures and replacing them with lighter aluminum versions and new electronics and weapon packages that would add back the weight and then some. The aluminum superstructure created a ship better equipped for that era’s battle-at-sea environment, but the aluminum also induced bimetallic corrosion at the juncture of the new superstructure with the steel main deck. This was a serious problem by 1973 when i assumed my duties. This was the tour where Earl Major and i reconnected while attending destroyer school and with both my destroyer and his cruiser, the USS England (CG 22) being homeported in Long Beach.

In case you don’t recall, one of my Navy tours was as chief engineer or “CHENG” on the destroyer, USS Hollister (DD 788). FRAM’s were WWII vintage destroyers “modernized” (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization) in the 1950’s and early 60’s by taking off the original superstructures and replacing them with lighter aluminum versions and new electronics and weapon packages that would add back the weight and then some. The aluminum superstructure created a ship better equipped for that era’s battle-at-sea environment, but the aluminum also induced bimetallic corrosion at the juncture of the new superstructure with the steel main deck. This was a serious problem by 1973 when i assumed my duties. This was the tour where Earl Major and i reconnected while attending destroyer school and with both my destroyer and his cruiser, the USS England (CG 22) being homeported in Long Beach.

When i arrived on board, the Hollister was forty-years old. The plant in those destroyers is still the most reliable ship propulsion system i ever experienced, especially for ships with the mission of war at sea. Duplication was everywhere and it was steam, steam, steam. Any electrical engineering equipment was backup or auxiliary. Those old greyhounds were small, fast, and durable. My vintage Hollister weighed in at 4200 tons and was 390 feet long and forty feet beam to beam. During one engineering full power trial, we built up the four boilers superheat and were still accelerating at 35 knots when we had to call off the dogs in order to make another commitment. i still have no idea what speed she might have reached.

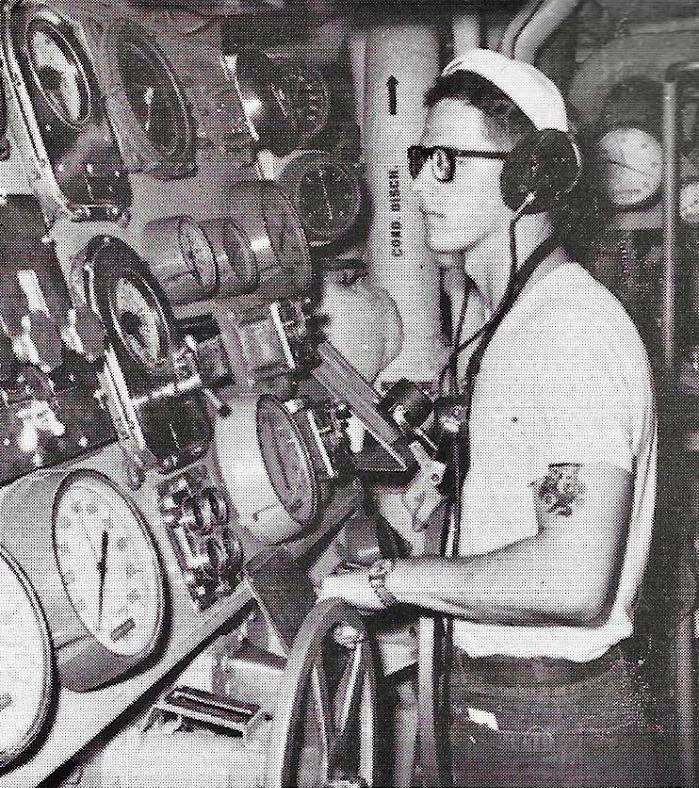

Main control and both the forward and after engine rooms were snarling, hissing, clanking, roaring webs of pipes and asbestos-lagged machinery, hotter than Hades and louder than the pits of a NASCAR racetrack or a flight deck during an A6 takeoff (and i know as i have been in all three places). The lower levels were mostly a swamp of pumps akin to a mechanical jungle. The entire engineering plant was quintessential Rube Goldberg. The heart was the main control board flats. We stood behind a wheel similar to the one in the hoax photograph as the machinist mates responded to the engine order telegraph from the bridge to funnel the appropriate amount of steam from the fire rooms through the turbines larger than a Ford Exhibition SUV to reach a finite RPM. When i climbed the ladder through the hatch to the main deck after general quarters or engineering drills, i was flushed and hoarse, feeling like we had just harnessed an untamed stallion and ridden him through a fiery desert, then him dragging us through a steaming jungle pond.

Ship’s propulsion was not my favorite endeavor on warships. i loved standing watches on the bridge, conning the ship, feeling the pitch of the bow into the waves — a primary reason i eschewed carrier duty — navigating by the “seat of my pants,” piloting in coastal waters and the harbors. i loved the deck evolutions of alongside replenishment, the gun shoots with 5″ 38’s booming in my ears, putting the boats in the water, and all of the boatswainmate endeavors. i also loved the dark, blue-lit hole of sonar and the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) plot where we detected and tracked submarines, watching the scopes and the fire control tracking while listening to the high-pitched beeps of the sonar transmissions and return echoes.

(Sometimes i would go into ASW on the mid (midnight to four a.m.) or the morning (four to eight a.m.) watches after my own watch on the bridge and, while one watch stander monitored the sonar search another sonar technician (ST) and i would “talk” to whales on the underwater telephone nicknamed “Gertrude.” The whales would talk back.)

But engineering was an awesome thing to behold. The machinist mates and the boiler tenders were working men in the fullest sense, giving themselves to incredible hours of hard labor to keep their beloved monster steaming safely. i appreciated and respected their knowledge, their experience, and their work effort. Even though i remained an officer-of-the-deck (OOD) and weapons oriented, that tour in engineering still brings a sense of satisfaction.

In the spring of 1974, my father took a very unusual solo trip to Long Beach. My mother stayed in Lebanon. i took Daddy down to Pier 9 at the Long Beach Naval Station where the Hollister was berthed. i gave him a tour of the engineering spaces, my domain. We went to the forward and after fire rooms, each containing two boilers the size of small two-story buildings and their intriguing support equipment through three levels of forced draft blowers, fresh and feed water tanks and cable runs, which would out cable a TVA dam plant. We went to both engine rooms with propulsion shafts with diameters the width of a one lane road and every conceivable pump one could conjure as well as a distilling plant (we called them evaporators or “evaps”) that defied logic. We visited the welding shop, the machine shop, the damage control lockers, and damage control itself, a plotting and communication hub for any emergency. When we emerged and headed back to my Navy quarters in San Pedro, my father seemed contemplative.

This man was a pioneer in many ways in the automobile world. he was acknowledged as one of the best, if not the best automobile mechanic in Wilson County, having started to work on cars in the late 1920’s. He drove his first car, his older brother’s, in 1924 when he was ten around the block and stopped it by hitting the garage gate because his legs couldn’t reach the brake pedal. He bought a junk car from a Cumberland law student in 1932 or so for ten dollars. He completely rebuilt the engine and the drive train, then constructed a wood chassis. He drove that on dates with my mother (and others) for three years and then sold it for ten dollars. In the sixties, he built a VW Beetle for my sister from two totaled wrecks, practically by himself including welding the good parts remaining from the two, doing all the engine work, upholstery, chassis, electrical. He knew more about the practical application of mechanics and engineering than anyone i have ever known, and at that stage of my Navy career, i had experienced college engineering propulsion professors and the elite officer and enlisted engineering community. He garnered my greatest respect.

i, on the other hand, had fallen into the engineering job through progression. i had been a sports editor, a disc jockey, a sub chaser, and a deck hand. Engineering was something i was passing through.

As we drove across the Vincent Thomas Bridge from Long Beach to San Pedro, Daddy finally spoke, “Jim, I would have never considered you would ever be the head of such a mechanical wonder. I’m proud of you and just a bit amazed.”

To this day, i am convinced the wrong James Rye Jewell was the Chief Engineer of the USS Hollister.

These ships too speed on 4 boilers was about 31 knots.

That was the “published” speed.